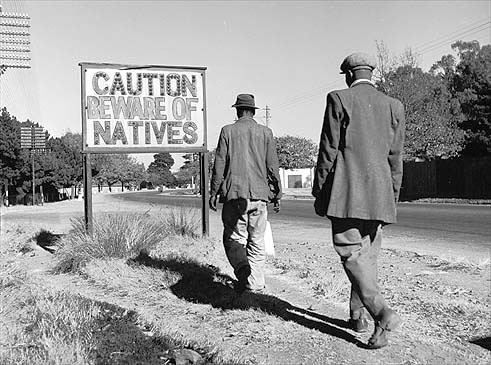

Would you be surprised to learn that this is a photo from the Apartheid era in South Africa? Do the words on the sign remind you of a history much closer to home?

To begin I’m going to make two general assumptions about Canadians. (1) Many Canadians know about the horrors of the Apartheid in South Africa and (2) Canadians generally feel empathy for the ongoing disparities between Black and White South Africans – and don’t question the Apartheid is to blame.

But in Canada do we hold the same regards for systemic barriers faced by Indigenous peoples?

It is easy to see how Canada prides itself in multiculturalism. Just look to the governments multiculturalism homepage. On it, you will see the missing piece to the puzzle is any honour or recognition to the First Peoples who live within these territories and the diverse cultural knowledge and practices they carry into today.

In Canada we have a clear tendency to disregard our more horrific acts – genocide and slavery included (Harris, 2012). This is particularly important given the Canadian Indian Act was a guiding framework to Apartheid practices in South Africa. The pass system originated in the Indian Act, was used to control freedom of movement by First Nations, much like it was used to govern Black people in South Africa.

Simply put, the Indian Act is a colonial tool that creates stifling Crown control over land, culture, economic opportunities, spirit, love, political structures, learning and education, rights and freedoms. First Nations have been resilient through this patriarchal oppression and continue to experience the effects of it.

In 1876 the Indian Act was accepted by the Parliament of Canada to assimilate Indigenous peoples by oppressing cultural, social and political practices. It consolidated the Gradual Civilization Act and the Gradual Enfranchisement Act (Hanson, 2009). A few policies within the Indian Act include the following (some have been amended or abolished, but intergenerational effects exist):

- the legal definition of someone as a “status or non-status Indian” – creating band membership,

- denying women status,

- the residential school system,

- the reserve system,

- a pass system that restricted First Nations from leaving the reserve without permission of the Indian Agent,

- enfranchising First Nations that attended University,

- forbidding First Nations from: potlatch and other cultural practices, speaking native languages, practicing traditional religions, accessing the right to vote (Joseph, June 2, 2015).

Here you can read the Indian Act in full, as it has currently been amended. This list is just a sampling to show how laws within the Act created a framework to legislate endemic poverty and prevent equitable Indigenous participation and belonging in society.

Furthermore, in over 140 years of the Indian Act, Indigenous peoples have protested it, fought for amendments to it, resisted its’ replacement with the assimilationist “White Paper” in 1969, and to this day continue to debate whether it should be abolished or amended (Coates, 2008). The Indian Act continues to be a controversial 76 pages, as explained by Cree leader Harold Cardinal in Unjust Society (1999):

We do not want the Indian Act retained because it is a good piece of legislation. It isn’t. It is discriminatory from start to finish. But it is a level in our hands and an embarrassment to the government, as it should be. No just society and no society with even pretensions to being just can long tolerate such a piece of legislation, but we would rather continue to live in bondage under the inequitable Indian Act than surrender our sacred rights. Any time the government wants to honour its obligations to us we are more than ready to help devise new Indian legislation. (p. 140)

Although the reach of the Indian Act is deep and harmful, it is clear that abolishing it is not a unanimous call to action. What is unanimously known is that Indigenous peoples experience colonial oppression in multiple ways today – as enforced through generations of the Indian Act.

P.S.: to see an informative TV show about the Act – this episode of The 8th Fire is a great place to start.

Next post: The Indian Act and the criminalization of Indigenous peoples today.

Sources:

Cardinal, H. (1999). The Unjust Society. 2nd ed. Vancouver: Douglas and McIntyre Ltd.

Coates, K. (2008). The Indian Act and the Future of Aboriginal Governance in Canada. Research Paper for the National Centre for First Nations Governance. Retrieved from http://fngovernance.org/ncfng_research/coates.pdf

Joseph, B. (2015, June 2). 21 Things You May Not Have Known About the Indian Act. Working Effectively With Indigenous Peoples. Retrieved from http://www.ictinc.ca/blog/21-things-you-may-not-have-known-about-the-indian-act-

Hanson, E. (2009). The Indian Act. Indigenous Foundations (University of British Columbia). Retrieved from http://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/home/government-policy/the-indian-act.html

Harris, D. (2012). Expanding our selective memory: studying black history reminds us of Canada’s impact on slavery–not all of which was good. Presbyterian Record, 136(2). p.4.

Picture: https://espressostalinist.com/genocide/apartheid-south-africa/